October 20, 2014

Note

from Arthur Obermayer, friend of the author:

In

1959, I worked as a scientist at Allied Research Associates in Boston. The

company was an MIT spinoff that originally focused on the effects of nuclear

weapons on aircraft structures. The company received a contract with the

acronym GLIPAR (Guide

Line Identification Program for Antimissile Research) from the

Advanced Research Projects Agency to elicit the most creative approaches

possible for a ballistic missile defense system. The government recognized

that no matter how much was spent on improving and expanding current

technology, it would remain inadequate. They wanted us and a few other

contractors to think “out of the box.”

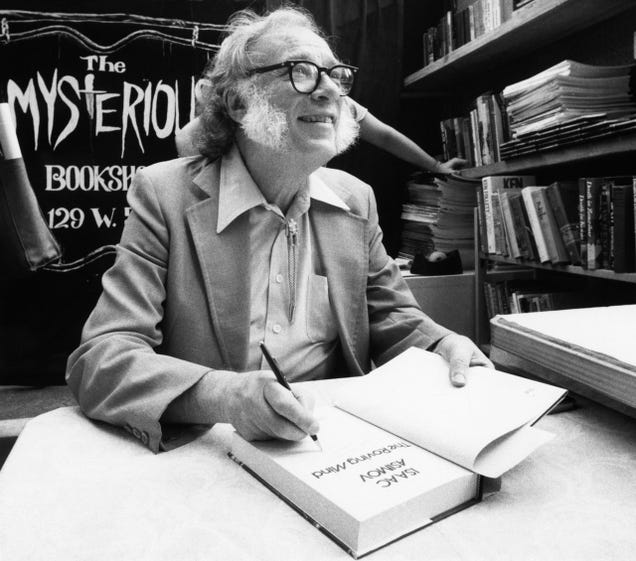

When

I first became involved in the project, I suggested that Isaac Asimov,

who was a good friend of mine, would be an appropriate person to participate.

He expressed his willingness and came to a few meetings. He eventually decided

not to continue, because he did not want to have access to any secret

classified information; it would limit his freedom of expression. Before he

left, however, he wrote this essay on creativity as his single formal

input. This essay was never published or used beyond our small group. When

I recently rediscovered it while cleaning out some old files, I recognized that

its contents are as broadly relevant today as when he wrote it. It describes not

only the creative process and the nature of creative people but also the kind

of environment that promotes creativity.

ON

CREATIVITY

How

do people get new ideas?

Presumably,

the process of creativity, whatever it is, is essentially the same in all its

branches and varieties, so that the evolution of a new art form, a new gadget,

a new scientific principle, all involve common factors. We are most interested

in the “creation” of a new scientific principle or a new application of an old

one, but we can be general here.

One

way of investigating the problem is to consider the great ideas of the past and

see just how they were generated. Unfortunately, the method of generation is

never clear even to the “generators” themselves.

But

what if the same earth-shaking idea occurred to two men, simultaneously and

independently? Perhaps, the common factors involved would be illuminating.

Consider the theory of evolution by natural selection, independently created by

Charles Darwin and Alfred Wallace.

There

is a great deal in common there. Both traveled to far places, observing strange

species of plants and animals and the manner in which they varied from place to

place. Both were keenly interested in finding an explanation for this, and both

failed until each happened to read Malthus’s “Essay on Population.”

Both

then saw how the notion of overpopulation and weeding out (which Malthus had

applied to human beings) would fit into the doctrine of evolution by natural

selection (if applied to species generally).

Obviously,

then, what is needed is not only people with a good background in a particular

field, but also people capable of making a connection between item 1 and item 2

which might not ordinarily seem connected.

Undoubtedly

in the first half of the 19th century, a great many naturalists had studied the

manner in which species were differentiated among themselves. A great many

people had read Malthus. Perhaps some both studied species and read Malthus.

But what you needed was someone who studied species, read Malthus, and had the

ability to make a cross-connection.

That

is the crucial point that is the rare characteristic that must be found. Once

the cross-connection is made, it becomes obvious. Thomas H. Huxley is supposed

to have exclaimed after reading On the Origin of Species, “How

stupid of me not to have thought of this.”

But

why didn’t he think of it? The history of human thought would make it seem that

there is difficulty in thinking of an idea even when all the facts are on the

table. Making the cross-connection requires a certain daring. It must, for any

cross-connection that does not require daring is performed at once by many and

develops not as a “new idea,” but as a mere “corollary of an old idea.”

It

is only afterward that a new idea seems reasonable. To begin with, it usually

seems unreasonable. It seems the height of unreason to suppose the earth was

round instead of flat, or that it moved instead of the sun, or that objects

required a force to stop them when in motion, instead of a force to keep them

moving, and so on.

A

person willing to fly in the face of reason, authority, and common sense must

be a person of considerable self-assurance. Since he occurs only rarely, he

must seem eccentric (in at least that respect) to the rest of us. A person

eccentric in one respect is often eccentric in others.

Consequently,

the person who is most likely to get new ideas is a person of good background

in the field of interest and one who is unconventional in his habits. (To be a

crackpot is not, however, enough in itself.)

Once

you have the people you want, the next question is: Do you want to bring them

together so that they may discuss the problem mutually, or should you inform

each of the problem and allow them to work in isolation?

My

feeling is that as far as creativity is concerned, isolation is required. The

creative person is, in any case, continually working at it. His mind is

shuffling his information at all times, even when he is not conscious of it.

(The famous example of Kekule working out the structure of benzene in his sleep

is well-known.)

The

presence of others can only inhibit this process, since creation is

embarrassing. For every new good idea you have, there are a hundred, ten

thousand foolish ones, which you naturally do not care to display.

Nevertheless,

a meeting of such people may be desirable for reasons other than the act of

creation itself.

No

two people exactly duplicate each other’s mental stores of items. One person

may know A and not B, another may know B and not A, and either knowing A and B,

both may get the idea—though not necessarily at once or even soon.

Furthermore,

the information may not only be of individual items A and B, but even of

combinations such as A-B, which in themselves are not significant. However, if

one person mentions the unusual combination of A-B and another unusual

combination A-C, it may well be that the combination A-B-C, which neither has

thought of separately, may yield an answer.

It

seems to me then that the purpose of cerebration sessions is not to think up

new ideas but to educate the participants in facts and fact-combinations, in

theories and vagrant thoughts.

But

how to persuade creative people to do so? First and foremost, there must be

ease, relaxation, and a general sense of permissiveness. The world in general

disapproves of creativity, and to be creative in public is particularly bad.

Even to speculate in public is rather worrisome. The individuals must,

therefore, have the feeling that the others won’t object.

If

a single individual present is unsympathetic to the foolishness that would be

bound to go on at such a session, the others would freeze. The unsympathetic

individual may be a gold mine of information, but the harm he does will more

than compensate for that. It seems necessary to me, then, that all people at a

session be willing to sound foolish and listen to others sound foolish.

If

a single individual present has a much greater reputation than the others, or

is more articulate, or has a distinctly more commanding personality, he may

well take over the conference and reduce the rest to little more than passive

obedience. The individual may himself be extremely useful, but he might as well

be put to work solo, for he is neutralizing the rest.

The

optimum number of the group would probably not be very high. I should guess

that no more than five would be wanted. A larger group might have a larger

total supply of information, but there would be the tension of waiting to speak,

which can be very frustrating. It would probably be better to have a number of

sessions at which the people attending would vary, rather than one session

including them all. (This would involve a certain repetition, but even

repetition is not in itself undesirable. It is not what people say at these

conferences, but what they inspire in each other later on.)

For

best purposes, there should be a feeling of informality. Joviality, the use of

first names, joking, relaxed kidding are, I think, of the essence—not in

themselves, but because they encourage a willingness to be involved in the

folly of creativeness. For this purpose I think a meeting in someone’s home or

over a dinner table at some restaurant is perhaps more useful than one in a

conference room.

Probably

more inhibiting than anything else is a feeling of responsibility. The great

ideas of the ages have come from people who weren’t paid to have great ideas,

but were paid to be teachers or patent clerks or petty officials, or were not

paid at all. The great ideas came as side issues.

To

feel guilty because one has not earned one’s salary because one has not had a

great idea is the surest way, it seems to me, of making it certain that no

great idea will come in the next time either.

Yet

your company is conducting this cerebration program on government money. To

think of congressmen or the general public hearing about scientists fooling

around, boondoggling, telling dirty jokes, perhaps, at government expense, is

to break into a cold sweat. In fact, the average scientist has enough public

conscience not to want to feel he is doing this even if no one finds out.

I

would suggest that members at a cerebration session be given sinecure tasks to

do—short reports to write, or summaries of their conclusions, or brief answers

to suggested problems—and be paid for that; the payment being the fee that

would ordinarily be paid for the cerebration session. The cerebration session

would then be officially unpaid-for and that, too, would allow considerable

relaxation.

I

do not think that cerebration sessions can be left unguided. There must be

someone in charge who plays a role equivalent to that of a psychoanalyst. A

psychoanalyst, as I understand it, by asking the right questions (and except

for that interfering as little as possible), gets the patient himself to

discuss his past life in such a way as to elicit new understanding of it in his

own eyes.

In

the same way, a session-arbiter will have to sit there, stirring up the

animals, asking the shrewd question, making the necessary comment, bringing

them gently back to the point. Since the arbiter will not know which question

is shrewd, which comment necessary, and what the point is, his will not be an

easy job.

As

for “gadgets” designed to elicit creativity, I think these should arise out of

the bull sessions themselves. If thoroughly relaxed, free of responsibility,

discussing something of interest, and being by nature unconventional, the

participants themselves will create devices to stimulate discussion.

Visit the MIT website:

No comments:

Post a Comment